Explore how the White House in Dagenham, east London, demonstrates the invisible qualities of creative spaces.

Social spaces that nurture togetherness and connection

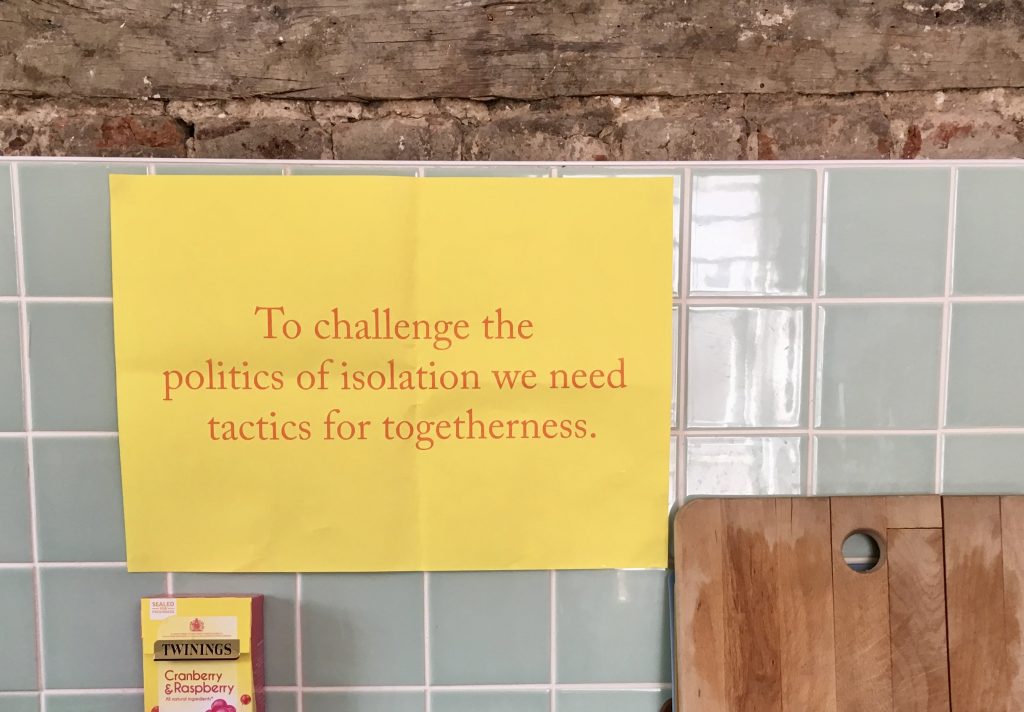

Reflecting on the invisible qualities of local community spaces is something that we do often at AKOU HQ. Community spaces are crucial for upholding social infrastructure. Such spaces not only provide an actual room to meet, but they also create space for people to nurture and develop the softer, intangible and invisible qualities that add to social life and an individuals lived experience. Such creative and social spaces nurture togetherness and connection. They help to build trust and self-confidence by supporting a sense of belonging and offering access to creative expression.

Whilst researching for my master’s dissertation in anthropology, I delved deep into the invisible qualities of infrastructure. The White House in Dagenham (east London) became a central case study of my research. It is a public space for art and social activity on the Becontree Estate.

The White House runs community-led programmes, supports local artists and creatives, as well as hosts national and international artist residencies. The White House practices socially engaged art, which includes any art form that provokes interaction, human connection and responds to people and places. Considering the current restrictions our communities face with regards to accessing spaces – like The White House – which build upon, transform and maintain our social connections – I thought it was important to share my observations from my time embedded in such a space. I want to talk about The White House’s a unique approach to holding space; and how art and being creative can help people to overcome so many things, even conflict.

Collaboratively designing and making a garden

In 2017 the artist collective They Are Here was commissioned to turn the car park behind the house into a community garden. They collaborated with a gardener and permaculture specialist, architects, local people and other artists to build a community garden. Collaboratively they designed the garden, removed tarmac, built a pond, created installations and erected a greenhouse.

During the participatory creation of this garden, different opinions came up. People shared their thoughts and comments on how the grass should look for example. Simple considerations such as how it might grow too high and how maintenance should be carried out. Like the wild grass, I observed standpoints chafing at each other, rubbing and producing friction between people.

Gardens form part of the environment we live in. They are cultural assets that display social values, but they are also a manifestation of social rules and norms. They present ideas of how we can use open, shared spaces. How a garden should look (and be taken care of) easily becomes a subject of highly charged discussion. The same holds for other dwelling spaces like housing. It is in the built environment that controversy manifests. Those deep convictions of what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ are easily revealed when building becomes a participatory process.

Building a space that allows for productive conflict

The garden project made space to question the unquestioned, the project promoted discussions around what is considered “normal”. It was a productive, socially engaged art project because it didn’t just focus on collaborative design and the building of the garden. But it teased out and stirred imaginations, opinions, and values. Political theorist Chantal Mouffe argues that conflict can be productive for society. The process of building the garden, despite the conflict it stirred, still seemed like a productive and necessary process for residents to take part in.

“It is not in our power to eliminate conflicts and escape our human condition, but it is in our power to create the practices, discourses and institutions that would allow those conflicts to take an agonistic form.”

Chantal Mouffe (2005): On the political. London: Routledge, page 130.

Following Chantal Mouffe, agonistic spaces are crucial for a diverse and rigorous democracy. And to her, art is particularly good at creating those agonistic spaces. The term “agonistic” emphasises the potentially positive aspects of conflict because it is coined by deep respect and concern for the other. The word has Greek roots; agon means struggle. It is a struggle that is important in itself.

Socially engaged art provides crucial infrastructure

By fully allowing the world in, The White House embraces different opinions and standpoints. Here, conflict and friction become productive. Socially engaged art always carries a potential for instability and friction, because it dares to engage in conversation, interaction and conflict. Thus, socially engaged art itself works as infrastructure. Through such art projects, The White House builds an invisible but crucial infrastructure. Also, it continues to transform that infrastructure according to people’s needs. The house maintains and cares for soft infrastructure, in turn, they truly support people in their everyday life.

Art and community spaces support connection, trust and care

When spaces like The White House are brave, open and governed by caring collectives, then they provide a social glue to society. This is now more important than ever before. As many such spaces are still closed, we become aware of the crucial role they play. The invisible qualities of community and art spaces nurture and enable crucial practices of care and togetherness to our communities. By creating agonistic spaces, they support and care for our relationships. Connection and social interactions always involve different standpoints and possibly friction. Finally, it is through mutual trust, participation and responsiveness, that they can teach us what it means when connection and care are radically prioritised. In consequence, they remind us of our interdependency; remind us that we thrive in relation to the world and the people around us.

Do you have any comments, questions or thoughts on this? Please get in touch: charlotte@akou.co.uk

1 See https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/stories/4-reasons-craft-good-your-mental-health.

2 See https://www.gov.uk/guidance/taking-part-survey.

3 The White House is located at the heart of the Becontree Estate, but predates the estate (which was built after World War I.). At the time of its construction, the estate was the largest social housing estate in the world; today, it still hosts half of all residents of the Barking & Dagenham.